My last post was a tribute to my father, full of heartfelt emotion and of vivid and not-quite-so-vivid memories. It was written impulsively. I had to get that material out of my system, to set down the full range of things that were going through my mind as a way to try to process them. There was a fear (however unfounded) that memories might flood away, like grains of sand through a sieve, if I did not set them down quickly. It felt an important priority to do that, as a way - I suppose - to manage the grief, to try to set some order around it. Attempting to proceed with life without doing this felt an impossible expectation.

I am now past the stage of needing to pour my heart out. Or, at least, I think I am. This is not to say that the experience of grief in recent days has been something like a simple stage-by-stage process. It hasn’t - and attempts I’ve seen to codify grief neatly into a step-by-step process don’t square at all with what I know. There’s something scientific-seeming and inauthentic about the Kübler-Ross model of the Five Stages of Grief, for instance. Naturally I recognise that the attempt to place some sort of objective scientific description around what can happen with grief may offer reassurance to others. But to me it simply exposes the flaws and limitations of this particular way of categorising human experience.

Grief as I have known it has been more messy, more existential, more visceral, and more jarring than a simple psychological framework is ever going to let on. It catches you unaware in particular moments. It leaves you alone for hours and then pervades all your thoughts.

At times it leaves you numb, emotionless, with a totally empty feeling. Psychologically ‘wooden’, is how I might try to describe this. It’s what Auden was gesturing toward, I think, at the beginning of his poem ‘Funeral Blues’. Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone…

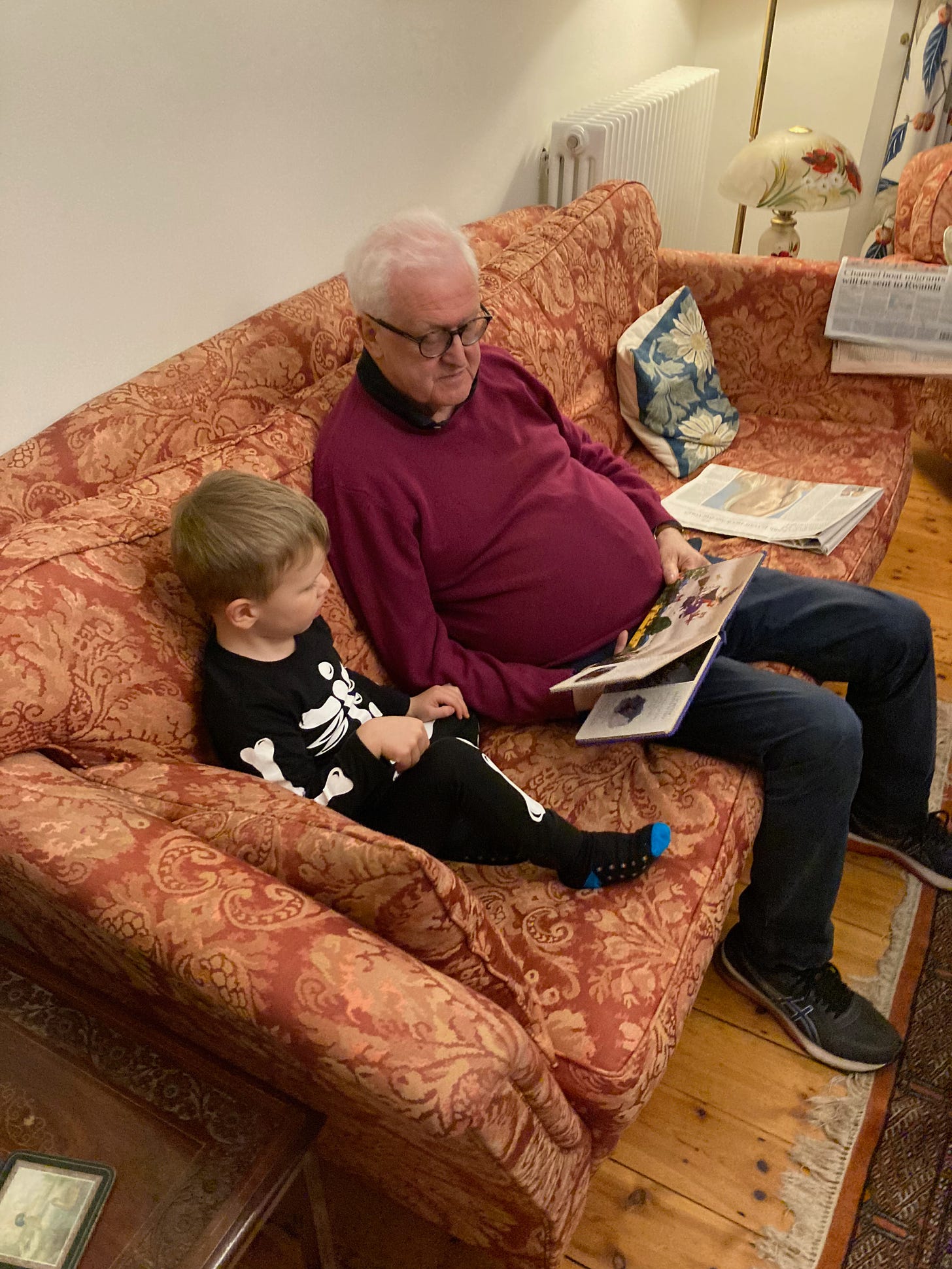

At other moments grief has produced tears, vulnerability, tenderness. Part of you needs a response, needs to be felt and known, needs to express itself. It can be triggered by unexpected things. Like trying to explain to your 3 year old what has happened to his beloved grandfather, and trying to puzzle out answers to questions like ‘Is heaven in the sky?’ and ‘I miss him. Can I see him? Can I hug him?’ The brute reality of how our emotional instincts (‘I miss him’) feed directly into our need for physical contact (‘Can I hug him?’) somehow seem quite self-evident to a 3 year old in a way many adults might struggle to articulate.

Grief means confronting a past which is no more, a past in which a treasured relationship still seems fresh and clear. You are now living in what feels a strange new reality, a reality in which this treasured relationship isn’t there anymore. You remember the person, the conversations, the feelings - and you still have them on your side of the relationship. You feel yourself reaching to experience them, as part of an ongoing two-way relationship, even now. But you have to start to accept that this isn’t possible, and that the relationship isn’t reciprocated any longer. Your reaching out is a gesture you will have to unlearn.

Another hard thing to accept is that the loss is not just of the past, but of the future. My children will never know my parents. There will be no more celebrations of life events with them, no more mentoring, no more support, no more kindnesses, no more meals and conversations. An awareness of a future lost brings into view for me the Horatian motto that one must seize the day, here, now; that one must really live and enjoy each moment one can. In doing this, one grows more deeply into a sense of one’s own mortality. A wise friend has told me that losing her parents made her realise something stark and grim: it will be her generation’s turn next. So, then, vivamus atque amemus: let us live and let us love. After all, as Horace puts it in his Odes, ‘omnes una manet nox, et calcanda semel via leti’: one night awaits us all, and the path of death is to be trodden just once.

These are the sorts of existential dimensions that have come into play for me in recent days. If a framework is to be sought within which to understand and process them, perhaps the experimental lens of a particular kind of philosophical writing can provide it. I think, for instance, of a chapter of Gillian Rose’s wide-ranging and sometimes highly compelling book Mourning Becomes the Law, and of her autobiographical text Love’s Work, which tackles the themes of loss, emptiness and grief in deep and interesting ways. I have turned to these books in recent days. One can of course point also to novels, poetry, literature. And indeed to spiritual writers. To Tolstoy, to Auden, to the Psalms. Paolo Coelho, perhaps.

Alongside these resources there has been the uneasy realisation that our culture does not readily provide the emotional and spiritual resources to deal with what we might call the ‘heavy’ moments in life. This is something that is brought out nicely at the start of Terry Eagleton’s book about religion, Reason, Faith and Revolution. There he notes that bright-eyed contemporary philosophy and public speech, in all of their most progressive forms - and for all their strengths, maintain an ‘embarrassed silence’, and a ‘crippling shyness’, on such vital matters as death, suffering, love, and so on. I share the view that the absence from our ordinary emotional vernacular, in the West, of deeply humanly satisfactory ways of articulating these experiences is a blot on our public discourse as much as it is a problem for healthy emotional life. More on this, perhaps, another time.

A final reflection for now is that there’s probably a good deal of truth in the saying that ‘when the going gets tough, the tough get going’. I have tried to remember that on a personal level. My father (and mother) would want me to thrive, to live well, to do good things, in spite of what has happened to them. I must do that. But the tough getting going also comes into play where family members and friends are concerned. It is indeed at tough times when the best of friends make themselves known - and I am fortunate to have a number of them. I have also come into contact with a good many new people these past weeks - in the hospital, and in other settings. As always good people offer a sense of consolation. Those who know how to make you see they care, and who know what to do about it and how to support: they are the ones who make everything possible in these moments in our lives.

I hope my next little piece will be a little more upbeat, a little more celebratory. Thank you to everyone who has been reading this one.

Nicely written. I would agree with your interpretation of the stages of grief. The theoretical description alone is never enough to fully describe what one experiences. I teach about them in nursing and have always struggled with their interpretation as well as the assumption that we all grief in a similar way.